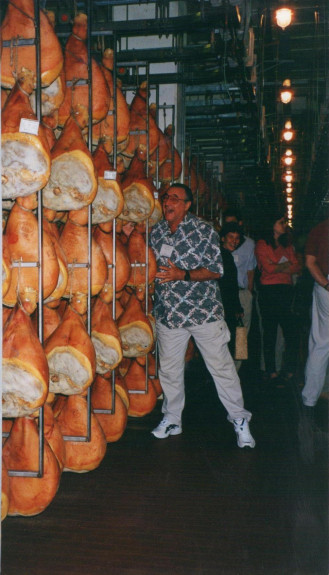

Our cooking class attendees had the occasion to visit both Parma and Modena in the gastronomically renown area of Italy, Emilia Romagna. It gave them the opportunity to view the production of the popular dry-cured ham known around the world as prosciutto as it was done centuries ago.

At 9 to 10 months of age, pigs are killed at the slaughter house and cut up, weighing approximately 150 kg each. The hind legs weighing on an average 10 to 14 kg are then dispatched to the factory for the making and storing in climate control warehouses. Both Modena and Parma factories use the same method and the exact three ingredients; salt, air and time to make their prized product.

One difference is that Modena, with a smaller number of production sights, services prosciutto mostly to Italy and the European Community made from their own local pigs. Parma that has 10 times more the number of production warehouses has become known throughout the world for its dry- cured hams. To supply the demand Parma has to buy pigs from other sources. The animals must meet certain required regulations to be accepted before production.

The first step is the salting of the leg. In Modena last month we noted the process of salting which involved rubbing a specific amount of sea-salt onto the leg, then after a week having it brushed off, then re-salted, and brushed off again. The salting process of approximately three weeks was called the winter stage due to the coldest refrigeration period of production.

The salt is used to preserve the leg against infestation, to give the prosciutto its silky texture, to keep it moist and to maintain the proper balance of sour and sweet. The legs were stored for about two months of winter before being moved upstairs to the spring season in temperature controlled rooms to meet the needs of the drying process and aging to start. After the process of salt absorption and weight falling, the leg will weigh approximately on an average about 7 kg.

The second ingredient, air, such as the excellent ecological and climate condition of this region with cool temperatures and low humidity, according to the producers in Emilia Romagna, creates the ideal environment for aging of the ham. The only difference in method from centuries ago is when drying occurred in the open air, not having today’s computerized climate controlled rooms. The one advantage of the past is that when aging outdoors one would not note as much as we did in our class, the stench caused by the loss of humidity on the 20.000 legs left to rest in one room for a few months.

The third ingredient, time, allows the proper amount of salt to be absorbed and its weight to fall both naturally and gradually to make a quality product. During the aging process the legs are lightly greased by hand with animal fat to close all openings, keep the prosciutto moist and prevent any small insects from penetrating the ham. In Modena a small one centimeter line between the outer skin and the fat was left to help in the aging process.

The aging of the legs takes place in controlled conditions at which time they are also tested for quality and categorized according to its salt, humidity and protein content before allowed to receive the seal of quality. Both locations are controlled by their consortium, branded if qualified, along with the history of each leg noted for the consumer to consider prior to purchasing. No additives or chemicals are added to the raw product, aged for a minimum of 10 months.

In a food culture nation such as Italy, the history of the animal is important to the consumer. First of all each animal is branded with a tattoo when young on his hind legs. That will be the identification of that animal throughout the process of being made into a prosciutto. Secondly, labeling on each leg verifies all steps in the process of production and demonstrates the history of the animal. In Parma, being that not all the animals were raised locally due to the demand of their prized prosciutto, the factory that we visited also had a third requirement. They specified prosciuttos they produced coming from pigs they did not feed.

Observed in our Parma class was how the factory differentiated prosciuttos from animals that did not have the advantage of having been fed the by- products of the parmigiano reggiano, that is made in the region. The whey and possibly some curd that is left from the cheese production is added to the feed of the pigs in this area. Parma and Modena factories claim this rich diet of the cheese -makers by- products is a factor responsible for the high quality of their products which is not available to animals fed outside of the area.

The advantage of all this history is if there should ever be a question of quality, a producer could immediately identify the source of the problem and the animal that produced the product. Hopefully this century old tradition of prosciutto making will continue for future generations to enjoy a product that is high in nutrition, low in calories, easy to digest, and rated number one in the world.