Mother, me and my aunt, one of the many relatives she sheltered and cared for from Italy.

Life was not easy for the immigrants. They left family and loved ones to settle in a strange country with a different culture, language and a society that often rejected them. Worse of all were the war years. Mom found herself in an apartment, alone, with three baby girls as Dad went off to work, coming home late at night. She dared not go out, having been warned to blacken the windows, not to let light in and live by candlelight, out of fear of bombardment.

I recall Mom making her own soap and candles in our kitchen, making sure that my sisters and I would not get near the hot pot of lye, one of the main ingredients. She made all our clothes as well as cleverly recycling my sister’s clothes into new designs for me. She was never taught but being creative, practical and out of necessity, learned to do it all. She never complained even though in Italy these chores were fulfilled by a large staff employed by her parents, feudal lords. Now it was up to her to do it all. It was especially difficult during the war years living in an apartment with three babies in a new country. At the age of 20 she left behind a large loving family, many wonderful friends, gardens of fresh produce, and acres of the countryside all hers to enjoy.

As a five-year-old I remember little, besides celebrating the end of the war. Mom and her friends filled the streets with American flags, confirming their adoption of the new country and its society. Not that they wanted to ever reject Italy, but they all wanted to make a better life for their children. We were told not to speak Italian and encouraged to live and do as the Americans. But the one thing we were warned not to adopt was the food of the “Americana,” and to never forget the family, the core and foundation of Italian life. It was a tradition carved in each of us, never to be forgotten, and reinforced by the paesani (other transplants.)

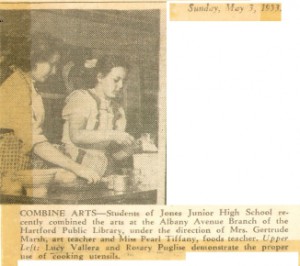

Teaching cooking in the 50’s. Never thought I would be doing it 60 years later.

Clustered together, these immigrants formed a community of their own, working together to solve any problems and considering themselves one big family. As a group this protected them, insulating them from the modern world of America. They were often criticized and insulted, facing prejudices as did other minority groups. What kept them going was their commitment to their extended family and their paesani, friends from the same place of origin.

Most were willing to work long hours, accept low wages, rival other immigrant groups, particularly the Irish, who had the advantage of speaking the language. Working hard all week meant they could revel in the simple pleasures of dance, music, food, and friends, sharing life and convivio at the table on weekends. We were to become Americans and learn the language, but it was reinforced daily to eat Italian food and enjoy convivio with family and friends. It was a simple inexpensive pleasure that we could enjoy.

As a typical Italian mother, Mom was deeply respected as the pillar of the family. Along with nourishing our family she was the emotional, spiritual, moral, and loving backbone of the Italian family. Believing there is no greater role than the noble work of raising a family with devotion and great pride, my Italian mother managed to always dispense food and advice along with love. This is a role that is losing its significance today, and in the process has changed the family structure and way of life.

Although buffeted by the winds of change, as many mothers are finding work out of the home, the Italian mother still tends to fulfill the traditional role of being in control of the domestic sphere and maintain the stability of the family. My mother always worked but never allowed her work to interfere with her primary role of being the heart and soul of the family, nourishing and nurturing her family with genuine foods and table life. Although generations apart, it seems that my best memories and my children’s best memories are most often of our experience of convivio, and understanding the need to reinforce it.

There is no question that Mom was a true Italian mother, cherished and essential to family life. Although a working mom, she invested much time and effort in making sure we ate well and together. Waking up at the crack of dawn to start breakfast, she managed to always include her rustic homemade country bread. None of that mushy packaged white spongy stuff ever entered our kitchen. For an Italian immigrant, accustomed to freshly baked bread, the commercially packaged product would not even be worth honoring with the title of bread. That is why the immigrants in the early twentieth century kept the tradition of home-baked goodies because of poor quality of products available outside the home. For those not exposed to quality it would not be missed. For those used to it nothing would suffice as a substitute. Italians have always had a heightened awareness of what they put into their mouths, very much the opposite of routine mindless eating often seen in America.

Mother, cousins and daughter preparing the polenta board

Our breakfast consisted of two eggs per person prepared differently unless oatmeal was served. On special days the aroma of Mom’s homemade cinnamon rolls would be our wake-up call, quickening our pace to dress for school. If too hurried to make her egg specialties, Mom could be seen beating two eggs for each of us with a shot of Marsala wine and a little sugar (never considering salmonella). Years later while making the gourmet dessert of zambaglione in my restaurant I had a flashback of my youth and realized that Mom was giving us was a shot of wine with our breakfast eggs. When I questioned her about this a few years ago she assured me it was just a drop and added, “It didn’t do you any harm, did it?” I would not suggest this for others to do, but felt worth noting. Certainly there was no need to sneak a drink in our house when you have a mother who serves her elementary school child Marsala, sweet wine, in a crystal glass on her way to school. Today, in America, she would be reprimanded for doing so.

Cereal, the breakfast of all my peers didn’t exist in our home. Mom did not know how to read the label but her motto was, “What you don’t see, you don’t eat.” I knew of nobody in those days that distrusted cereal. She could not understand how it could sit on the grocery store shelf for months. Something had to preserve it, be it salt or sugar. I never could understand why we could not eat like the Americans. All my classmates ate the cereal, which was promoted as a healthy and easy-to-prepare breakfast. Years later I learned that Mom was partly right, considering the quantity of salt and sugar that is often hidden in cereal to keep it on the shelf.

I left Newport Beach California for this??? Mother taught me years ago how to can tomatoes.

I remember trying to convince Mom that there was nothing wrong with the new, frozen, “just add water” orange juice in a green label can that became very popular in my youth. Her answer was “Just eat the orange,” pointing to the large bowl of citrus, a permanent fixture on our dining room table, followed by “Do you know what is in that can? If you want juice, here is the juicier, squeeze.” I never forgot that day. In fact, I recall so well, squeezing one night for the morning, and Mom asking me, “Why do it now? Don’t you have time in the morning?” Did she know that it might be more nutritious freshly squeezed?

My Italian lunch bag was always an embarrassment for me in grammar school. I used to hide my sandwich since all the others had peanut butter and bananas or for variety, peanut butter and jelly on their store bought spongy bread. Why did I have to be different? Mom also made sure we had variety. Besides prosciutto, salami, homemade sausages, and all kinds of cheeses, there were major varieties due to our dinner leftovers: roast beef, tongue, pork, sweetbread, or brain croquettes sandwiched between Mom’s homemade bread. On Fridays, since we could not eat meat as practicing Catholics, our sandwiches might consist of grilled eggplant, zucchini, tuna fish, frittata, cheese, or greens such as Swiss chard from grandpa’s garden, along with our dessert picked that morning from one of his fruit trees. On very special days, we had the treat of finding Mom’s homemade oatmeal cookies filled with raisins along with fruit from our garden.

While eating I would try to hide the inside of the sandwich so that I would not have to answer that frequently asked question by my classmates, frowning with disgust, “What is that?” It was only in high school that my sandwiches started to become popular, and I had a chance to taste my very first peanut butter sandwich on a trade. I found it to be strange, yet wanting to be popular, traded it occasionally, giving up homemade sausage sandwiches covered with roasted peppers for this thing that came out of a jar, was smeared on soggy spongy white tasteless bread. I realized after a few trades that the soft bread and filling of peanut butter tended to leave me hungry the rest of the day. I missed Mom’s thick slices of crusty fresh country bread with filling so good that it never needed a dressing of hidden calories. She felt, as most Italians, that if the product was good, you didn’t need to disguise it. If a filling needed a little help, a few drops of mom’s olive oil would take care of it.

Dinner for us always included vegetables from the yard or if out of season, from our family basement, our “personal supermarket.” Beans picked in the fall and put aside to dry were saved for consumption during the winter months. They were commonly included in our dinner, always a different variety and preparation. Beans were a necessity and the salvation for many. Besides meeting dietary needs beans met the needs of a limited budget, and were often called upon to substitute for meat. Most Europeans consume a variety of beans in their daily diet, a healthy protein as well as carbohydrate. What was available and usually purchased in my youth by most Americans was a canned product marketed as beans yet having “pork fat” as one of its main ingredients.

Now there is nothing wrong with good beans or good pork, but when tasting it for the first time at a dinner years later in my university sorority house, my mom’s words came to mind: “What you don’t see (in the can), you don’t eat.” As my sorority sisters enjoyed with gusto canned beans served before them, I realized how Mom was right. My sorority sisters never had Mama’s beans, didn’t know better, familiar only with the canned product. I, on the other hand, could not taste the bean only the sweetened , fatty, greasy, gooey liquid that covered what I guess were beans. Did these ladies even know the taste of a bean? Leaving them on my plate caught the attention of one of my classmates who asked me if she could eat them if I didn’t want them and added, “Aren’t they delicious?” I didn’t answer but handed her my plate. I longed for Mama’s beans, freshly prepared without any of that added goo.

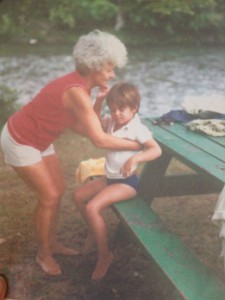

Mother the pillar of our family here with her youngest grandson Jason at age 5, and today with her youngest great grandson Dante at age 5. Passion for family is obvious.

Finally beans are being recognized in America as a most valuable food item. Once one experiences the simple preparation of the basic product, as confirmed by attendees in my cooking classes requesting my famous bean recipe, one can understand quality. A principal cause of bad eating choices in our society today is the lack of experience with genuine foods. Meat, usually a roast on Sunday, was always thinly sliced, dressed with natural juices, and complemented with the vegetables and onions that would cook along with it in the pan. Mom did not know about using flour to thicken gravy soups or sauces. She might chop a carrot or celery if sauce needed sweetening or puree if it needed thickening. Utilities being expensive, when she used the oven she made sure she put the vegetables in as well, to cook along with the meat. Pasta served only on Thursday and Sundays was always freshly made with good semolina wheat. Preceding the usual light soup course were nibbles of fresh fennel, carrots, and celery that mom had in the center of the table along with a little dish of her sister’s homemade olive oil sent from Italy. Waiting for dinner we would dip the vegetables into the olive oil while talking to Mom about the day’s events. As she finished preparing the meal the aromas of her kitchen would lead us to peek into the pot on the stone or in the oven to see what it was causing us to salivate in anticipation of her homemade meal.

Diet and calories were words unfamiliar to mom and never mentioned in our upbringing. There was no scale for daily weighing. Food was to be enjoyed. A meal was never skipped and no family member was ever absent from the table unless ill or out of town. No excuse. Even as a twenty-five-year-old, dating my husband-to-be, he had to ask my father for special permission to allow me to be absent from the evening meal. Dad’s answer, typical of Italians, was “Why can’t you join us for dinner?” Such is the Italian family like a Chinese family always ready for an extra person. Just add another antipasto dish. Not to worry, our cellar would always meet unexpected needs. It is unusual for an Italian to send someone away from the table. Etiquette says you do not bother a family during the sacred dinner hour but if you arrive at that time plan to stay.

I recall buying chickens with dad at a chicken farm where dad knew of course the owner, knowledge of the feed, the environment, and the care given to each bird. He would select one and help with the killing and plucking followed by Mom singeing any remaining feather follicles at home. I am always reminded of this smell when singeing my hair on a curling iron stuck on my head as strands of hair fall to the floor. When having to buy a chicken away from the farm, dad reminded me to always be sure to buy chickens with their heads on. How else would you know how fresh it was? Just as he taught me to always check the eyes of a fish to be reassured of freshness.

When I moved part time to Italy in the early 80s, chickens at our countryside meat market were sold with their heads attached. This custom began to change in the 90s with the coming of the big supermarkets, globalization, and foods from around the world. Holidays were a memorable event which included all of the extended family. As with most Italian families, Dad might have the big yard but there was always an uncle to supply the homemade brew of grappa, another to supply the wine, and Grandpa always arrived with a basket of fresh fruits from his garden. Aunts might bring their specialties of homemade pastries, all of which contributed to making the event a great success. Fresh pasta was always part of the meal made by Mother, who seemed to do it with such little effort. It never seemed like work for her.

95 years difference, mom at 100 and Dante at 5

I loved watching Mom with the yard-long rolling pin stretch the dough into a paper- thin circles measuring more than a yard in diameter. Mom would then roll two sides to the center creating a roll of dough soon to be attacked by her big knife creating thin strips of tagliatelli. As kids, we all helped put the pasta on mop poles balanced between two chairs to allow the pasta to dry. I eagerly anticipated the times when our entire family would work together on a project be it to make sausages, bake cookies for a wedding, prepare dishes for a funeral or a holiday family get-together. There was always some kind of music to accompany each work project. It might be my aunts singing out of tune some old Neapolitan song, a relative on the accordion, Dad singing an aria from an opera, or a guitar player accompanying the kids who would join in with the few Italian lines they knew such as “funiculà, funiculì, funiculà.”

Mom and her first friend that she met in America in 1933, my sister’s mother -in- law, Amy, from Connecticut, going for a walk at age 100 and 102 in California, Wonderful ladies and mothers.

With the meal eaten, the table cleared, and the tablecloth shaken outdoors to free it from dinner crumbs, the women would all work together to wash and put things away so that they could play their game of tombola (bingo) in the kitchen. A large platter of fresh fruit and a bowl of mixed fresh nuts in their shells would now take the omnipresent role at the center of the kitchen table, which was previously occupied by dad’s homemade table wine and olive oil. One of the women would start making espresso which would signify the end of the meal. Homemade cookies might join the fruit and nuts, as the espresso pot wafted the aroma of freshly roasted coffee beans. Coffee cups for the men at the dining room table would be placed in the center along with bottles of liquors, such as anisette, grappa and sambuca, so-called digestives.

Money may have been scarce, but fun was always in abundance. Enjoying meals with family and friends was a ritual of pleasurable experiences for children. Similar associations in adult life often trigger fond memories and emotions that last forever in our memories. These cultural practices and experiences can condition one to seek them out in life, but only if fortunate to have been enriched with these traditions in their upbringing. It saddens me to see the globalization of the world endangering these memories of gastronomical culture, and begin to forfeit quality food for quantity and the “no time” virus of convivio.

Class reunion, seeing friends for the first time in 50 years.

A few years ago, flying to the States to attend my fiftieth class reunion, I was surprised how everyone remembered me as the Italian kid with the great cellar and garden. Memories came to mind of the end of the school day, when my friends would walk me home and stop in the garden to enjoy the grapes from the vines that formed a pergola over our long garden table where we enjoyed so many meals, al fresco. Others told about picking great white peaches from an old but prolific tree in our garden and how they missed it when it was struck down by lightning. I still yearn for those peaches that no commercially sold peach can match in taste. Others remembered the big wheel of parmigiano cheese they enjoyed stabbing with the parmigiano knife found resting in its place on top of the 10 pound wheel. Friends mentioned how I had introduced them to real parmigiano. They were familiar with a grated cheese purchased in a green can that was labeled parmigiano. My parents and their Italian friends refused to call it anything but sawdust.

When leaving the reunion and saying our farewells, a classmate I did not recognize at first called me by name and commented how he had never forgotten how sad it was when I left for Italy that summer of 1949. When I asked why, he explained in my absence he could not go over to the house and slice the prosciutto, which permanently took its place on the slicing machine in our kitchen, or break off links of sausage hanging in the cellar. He missed stopping by to see the family sitting at that long table in the yard which always led to an invitation to join the family at the table. I then recalled the man before me. He was the Jewish kid whose faith my mother had questioned some sixty years ago. At the time, he told my mother that if he didn’t know it was pork it would be ok to eat. I wonder if my classmates would have remembered me if it were not for my mom’s kitchen, grandpa’s garden, and my father’s cellar, our Mediterranean Diet in Connecticut.